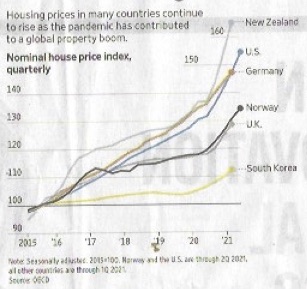

The record-setting rise in home values during the pandemic is triggering fresh debates about housing affordability worldwide, as policymakers search for ways to rein in price appreciation without driving prices sharply lower or derailing the global economic recovery.

P rice increases have been a boon for many families. Rising home values typically spur more spending on furniture and other goods, benefiting the economy at large.

rice increases have been a boon for many families. Rising home values typically spur more spending on furniture and other goods, benefiting the economy at large.

Recent events in China are a reminder of how tricky it can be to try to tame the market. Chinese leaders, worried that rising housing costs could trigger unrest and add risks to the financial system, have moved to curtail price increases and rein in borrowing.

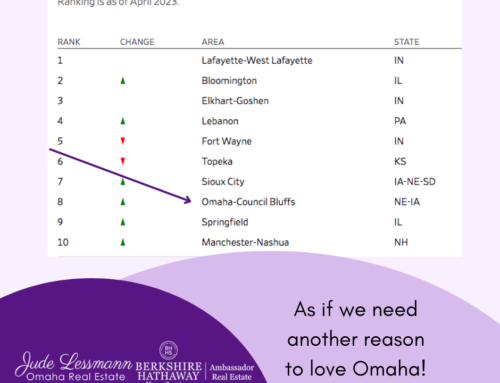

That has prompted buyers’ complaints across North America, Europe, and parts of Asia. Australian lawmakers recently opened an inquiry into housing affordability.

“It really shouldn’t be this hard,” said Herlander Pinto, a 32-year-old software engineer, who recently bought a house with his partner in a Toronto suburb farther from the city than they wanted. “We just had to hope that somebody with deep pockets didn’t come along and put in an outrageous bid.”

In Canada, New Zealand, and Norway, the home price-to-income ratio—a measure of affordability that is house prices divided by disposable income—is at its highest level ever, according to data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Elsewhere, including the U.S. and France, price-to-income ratios are climbing.

“In Auckland, anyone who’s owned a house for the last seven or eight years is now a millionaire,” said Ben Hickey, chief executive at mortgage broker HomeBoost Mortgages NZ, referring to New Zealand’s biggest city. “Then you’ve got the other half of Auckland who don’t own a house and are really wondering what they’re going to do.”