It’s long been our superpower in the fight for jobs and workers: You pay less to live in Omaha.

The cost of living in the Omaha metro area historically rated as a bargain nationally — a spending power so strong it could keep more money in your pocket or buy you more at the store. As recently as 2013, Omaha’s cost of living was fourth-lowest among the country’s largest metro areas.

But Omaha’s economy has quietly experienced a shift: It’s not always so cheap to live here anymore.

New figures show Omaha’s cost of living has risen in recent years, and the metro area’s vaunted spending power has fallen behind some of its competition.

It’s a red flag for a local economy that is suffering from a workforce crunch and a city that often watches its talent move away.

Combined with the market for salaries in Omaha, an unsightly combination of factors could be emerging.

Omaha has long paid relatively lower wages to workers — lower than the national average and some of its neighboring competitors — but could fall back on the low cost of living to sell the pay. Now, figures analyzed by The World-Herald show Omaha offers relatively lower pay — with a growing cost of living.

For an individual’s bottom line, the shift means your dollar doesn’t stretch as far as it used to, said David Drozd, research coordinator for the Center for Public Affairs Research at the University of Nebraska at Omaha.

As recently as 2013, a typical salary in Omaha effectively got a $5,000 to $6,000 boost because of the lower cost of living, Drozd said. As Omaha’s cost of living index rises, that bump might look more like $2,000 or $2,500, he said.

“It kind of takes some of that selling point away,” Drozd said.

The shift has gotten the attention of the Greater Omaha Chamber of Commerce, which has keyed on the city’s workforce shortage and is looking at ways to address the problem.

David Brown, the chamber’s president and CEO, said that among the questions the chamber has asked: Is Omaha’s cost of living low enough to provide a rationale for paying relatively lower wages?

“Our analysis tells us, ‘No, it’s not,’ ” Brown said.

Naturally, Omaha is challenged to draw people to a city without stunning views — no mountains, no oceans. But the chamber has played off that by pitching Omaha’s hardworking attitude with the slogan, “We Don’t Coast.”

Omaha can tout good schools, low crime, being a great place to raise a family — a prime spot in The Good Life state. It has good food, good entertainment, a startup culture and headquarters for four Fortune 500 companies.

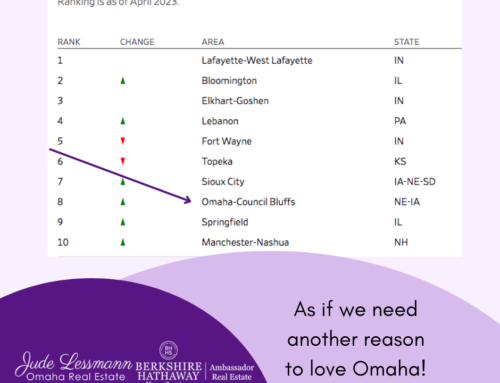

The city shows well in marketing list after list: No. 1 city for college grads to start their career, No. 1 best metro area for millennials, No. 2 best small city, No. 3 in economic opportunity, No. 5 city where employees are happiest, No. 6 lowest cost burden for renters, even No. 7 among the best affordable places to live for housing.

But that No. 7 ranking with U.S. News and World Report fell from No. 2 last year, and the report dinged Omaha because it “has seen a slight increase in its cost of living.”

Much of the rising cost of living is attributable to Omaha’s increase in housing costs, both to rent and buy.

In Omaha’s hot housing market, the price of a four-bedroom, 2,400-square-foot home has increased from $227,000 in 2011 to nearly $295,000, and the principal and interest on a mortgage has increased 23 percent, according to figures tracked by the Council for Community and Economic Research.

The supply and demand in the Omaha market have combined to progressively increase home prices — demand among buyers is high, but the supply of homes available hasn’t kept up.

The average apartment rent for a newer, two-bedroom unit is up 61 percent in that time — from $676 a month to $1,086. That translates to an eye-popping $4,920 more a year to rent in Omaha.

In Des Moines, the increase in housing costs is much less pronounced. Rent there now costs about what it did in Omaha seven years ago, meaning a typical Des Moines apartment dweller saves about $4,900 a year versus renting in Omaha.

In the past year, Omaha’s rating also has been affected by higher gas prices and higher-than-average taxes and fees on cellphones, said Jennie Allison, program manager for the Center for Regional Economic Competitiveness and manager of the Cost of Living Index.

On cellphones, the Tax Foundation says Nebraska’s cellphone taxes and fees are fourth-highest in the country, amounting to about a quarter of the bill.

On gasoline, figures in the index reflect a jump in prices. Figures from AAA show the average annual price of a gallon of gas has increased in the metro area nearly 52 cents since 2016.

Even so, Allison said Omaha’s relatively low cost of living compared with other large cities remains useful for attracting people.

“That’s still really great,” she said.

So it’s true Omaha remains a bargain compared with big cities on the coasts. And we remain below the national average; Omaha’s cost of living is 95 percent of what’s typical across the country.

But we’re slipping with our closest Midwestern competitors.

Omaha used to be well below Kansas City’s cost of living. But we’re even now, and Kansas City has the advantage of higher salaries — an $1,800 higher average salary in K.C.

—Courtesy of Omaha World-Herald